March 13, 2023

Death and Miracles

2 Kings 5:1-15 and Luke 4:24-30

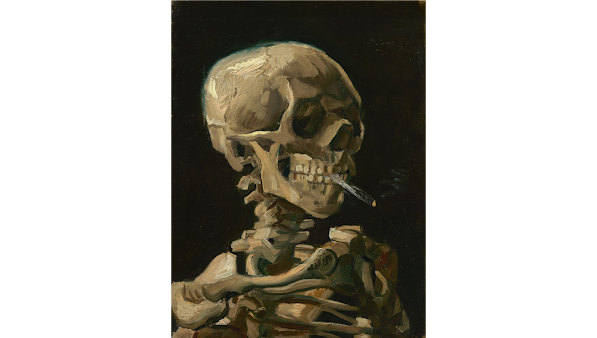

Lent is a time of thinking about death. We contemplate the sin and suffering in the world and our own inescapable mortality; we prepare for the betrayal and death of Jesus Christ.

Yet it is also a time of thinking about miracles. We approach Good Friday knowing that Easter Sunday awaits. Contrary to the evidence of science and our own experience, we proclaim that Jesus was dead and yet now is alive forever.

This is a pretty great deal. Yet the two passages for today suggest that we humans can become volatile indeed when brought face-to-face with death and miracles. In the Old Testament, the Syrian commander Naaman has what can only be described as a temper tantrum when the prophet Elisha does not perform any dramatic flourishes to heal him from leprosy, but instead commands him to bathe in the Jordan River. Centuries later, Jesus informs his synagogue that he is the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy, but he will not perform miracles for them such as he did in Capernaum (where he healed practically the whole city from disease and demons; see Mark 1:30–34). In response, the worshippers at the synagogue become enraged and try to throw him off a cliff.

When viewed in this light, these stories raise two main questions. The first is simple: Why do these people get so angry?

I suspect they do because, in general, our species likes to understand and control as many things as possible. Miracles and death do not let us, for they are mysteries. Death is the final frontier of knowledge; we have no way of knowing what happens to us after we die. This is one reason why we dread it so much. Naaman’s leprosy, and the many diseases that no doubt afflict the worshippers in Jesus’s synagogue, do not just torment their victims with pain, but with the promise of death. The only way to escape their fate would be, well, a miracle.

Miracles have a more positive connotation, but they, too, are utterly outside our influence or comprehension. If they were not, they wouldn’t be very good miracles! Yet in these two stories, Naaman and the worshippers at the synagogue grow furious when they are told that the miracles on offer are not on the terms they expected; the miracles are outside all geographical boundaries and human frameworks of knowledge and power. They are salt in the wounds of these people already powerless under the shadow of death.

Now, I don’t think it’s their anger itself that is the issue here. Anger is an extraordinary engine that gives us the drive and courage to make a better world. It seems a valid response to being told, “I can heal you, but…”. But in both stories, these people let their anger carry them to destructive actions that, ironically, almost defeat the very purpose they are trying to defend. If Naaman had refused to bathe in the Jordan on principle, he would not have been healed. If the synagogue had succeeded in shoving Jesus off a cliff, they would have cut short a ministry that would ultimately save them and the entire world from death everlasting. Their unbridled, unconsidered fury leads them to try to turn these miracles into something they understand and control: into no miracle, in Naaman’s case, and into a murder, in the crowd’s. They are unwittingly working to undo the bigger miracles undergirding the darkness they are trying to escape. It says a lot about God’s love that, despite such rage, both stories have happy endings.

But this brings us to the second big question that the stories raise: Why can’t Naaman bathe in the waters of his own country? Why won’t Jesus heal the members of his own synagogue in his own hometown? In short, why can’t we all be the recipients of miracles on our time and on our own terms, if we are supposed to be the children of a loving God? Why instead are we still shadowed by death?

And by asking this question we become Naaman waiting at Elisha’s door, we become the worshippers sitting in the synagogue as Jesus declares his identity to them. Because we simply do not know the answer. We do not know the ending to our story and thus cannot trace the logic underneath it the way we can in a tale that we read in a book. We only can ponder the stories that we have been given, and try to learn from them, and from that foundation choose how we react to the mysteries that we encounter.

But as we go through our Lenten lives where death feels ever present and miracles so far away, I hope we can all remember to look for the miracles in the darkness of everything we cannot hope to control or understand. Because we are a resurrection people, and we are promised even in these strange passages that there is healing and life waiting beyond death. Lent reminds us that we are in the hands of someone who has entered into the middle of these mysteries and mastered them. We are safe to grieve, to be angry, to live, to die, and to rise from the dead in his hands.

Especially if we don’t try to throw him off a cliff.

- Rachel Robinson

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment